Home

Home

Tutorial

TutorialRun pyspread with

$ pyspread

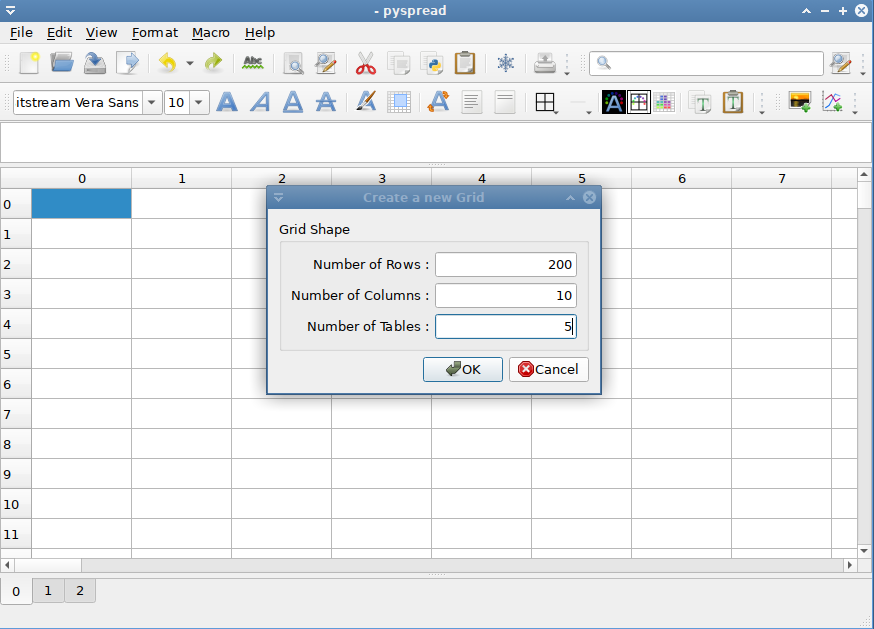

Select the Menu File → New Enter 200 rows, 10 columns and 5 tables in the pop-up menu.

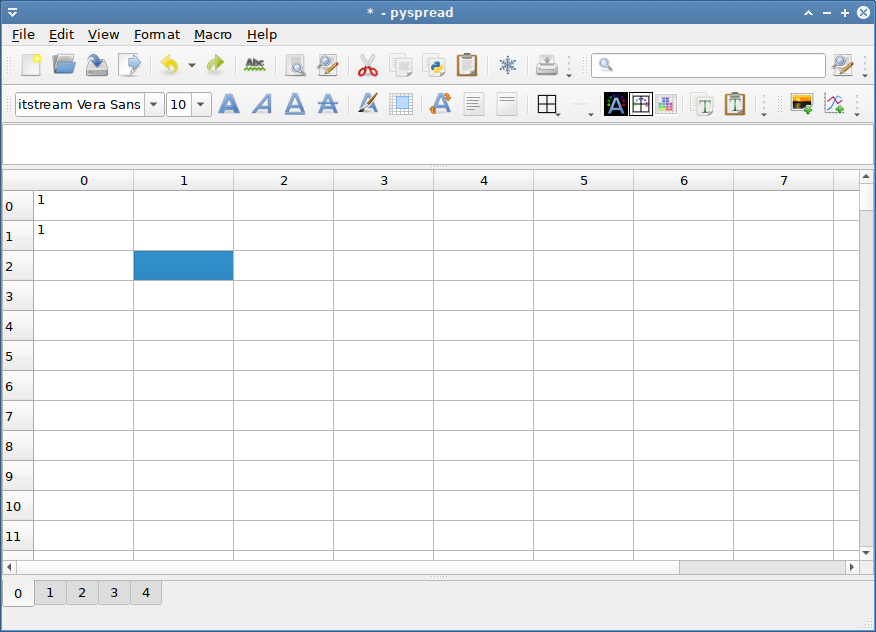

After clicking OK, you get a new table with the typed-in dimensions.

Select the top-left cell and type:

1 + 5 * 2

The spreadsheet evaluates this Python statement and displays the result: 11

In the cell that is one row below (cell (1, 0, 0)), type S

As we see from the result, S is a known object. In fact, it is the grid object that we are currently working in.

To access a cell, we can index the grid. Replace S with

S[0, 0, 0]

and the same result as in the top-left cell that has the index (0, 0, 0) is displayed.

Now replace the expression in the top-left cell by 1.

Both cells change immediately because all visible cells are updated.

The main grid S can be sliced, too. Write into cell (3, 0, 0): S[:2, 0, 0]

It now displays [1 1], which is a list of the results of the cells in [:2, 0, 0].

Since cells are addressed via slicing, the cell content behaves similar to absolute addressing in other spreadsheets. In order to achieve relative addressing, three magic variables X (row), Y (column) and Z (table) are used. These magic variables correspond to the position of the current cell in the grid.

Change to table 2 by selecting 2 in the iconbar combobox. Type into cell `(1, 2, 2):

[X, Y, Z]

The result is [1 2 2] as expected. Now copy the cell (Crtl-C) and paste it into

the next lower cell (Ctrl-V). [2 2 2] is displayed. Therefore, relative addressing is achieved. Note that if

cells are called from within other cells, the innermost cell is considered the current cell and its position is returned.

The easiest method for filling cells with sequences is using the X variable.

X - 1Then copy cell (1, 1, 2), select the cells (2, 1, 2) to (99, 1, 2) and paste via

Cells can be named by preceding the Python expression with “

Type into cell (2, 4, 2):

a = 3 * 5

and in cell (3, 4, 2):

a ** 2

The results 15 and 225 appear. a is globally available in all cells.

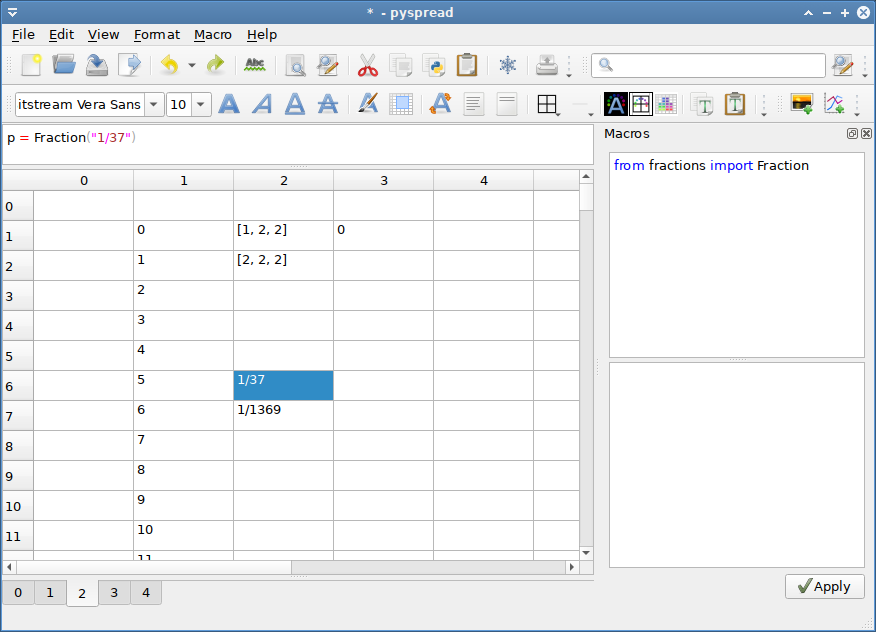

External modules can be imported into pyspread. Therefore, powerful types and manipulation methods are available.

Open the macro panel with <F4> and type

from fractions import Fraction

Then press the Apply button.

Now we define a rational number object in cell (6, 2, 2) :

p = Fraction("1/37")

and in cell (7, 2, 2)

p**2

The result 1/1369 appears.

Summing up cells: The sum function sums up cell values. Enter into cell (16,2,2):

sum(S[1:10, 1, 2])

yields 36 as expected.

However, if there are more columns (or tables) to sum up, each row is summed up individually. Switch to table 1 and enter

1 into cell (0, 0, 1)2 into cell (1, 0, 1)3 into cell (0, 1, 1)4 into cell (1, 1, 1)sum(S[:2, :2, 1]) into cell (0, 4, 1)Cell (0, 4, 1) yields [3 7], which may not be intended. If everything shall be summed, the numpy.sum function has to be used:

numpy.sum(S[:2, :2, 1])

which yields 10.

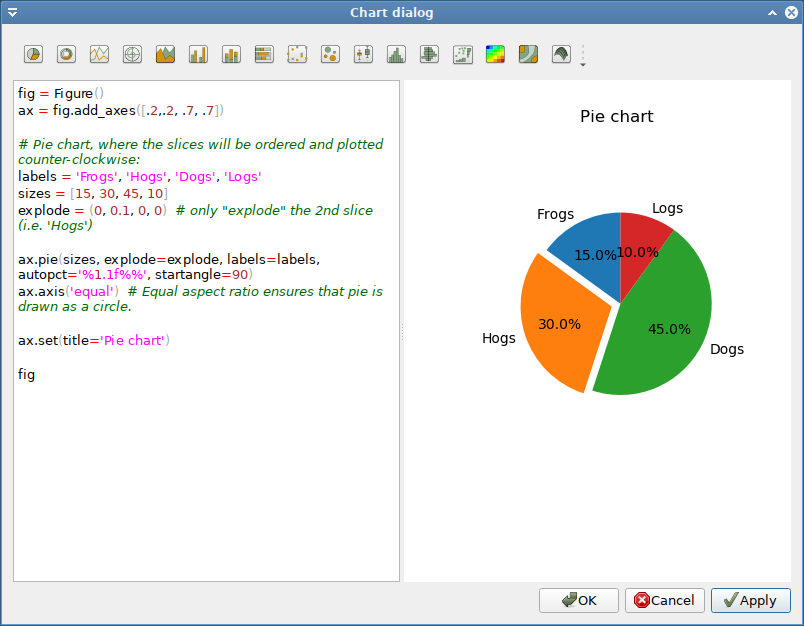

Pyspread renders a plot in any cell that returns a matplotlib figure. Merging the cell with other cells can increase plot size. In order to make generating plots easier, a chart dialog has been added to the Macros menu. This chart dialog generates a formula for the current cell. This formula uses a pyspread specific function that returns a matplotlib figure. You can use the object S inside the chart dialog window.

Switch to table 3. Select cell (0,0,3).

Select Insert chart from the Macro menu.

On the left side, Python code can be edited. On the right side, a chart can be displayed as soon as the code delivers a matplotlib figure in the last line.

In order to make things easier, examples are provided that can be inserted into the editor by clicking on one of the toolbar buttons.

Select the rightmost button (Pie chart) and press the Apply button. A pie chart is displayed on the right panel.

Press the Ok button. Now the chart appears in cell (0, 0, 3). However, it is tiny. To increase size, select all cells from (0, 0, 3) to (8, 4, 3) and select Merge cells from the Format menu.